Sandy and I will be traveling during the first three weeks of April. We are “repurposing” a blog originally published in 2015 under the title of Jacques the Ripper and again in 2018, but in an expanded format under the new title of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Both titles are appropriate as our topic today is about a serial killer who passed himself off as a member of the French Resistance during the occupation. About the only difference between Mr. Hyde and Dr. Marcel Petiot is that Petiot did not drink serum to transform himself into the serial killer — he did it all on his own. His two Paris residences have been included as stops in volumes 1 (page 86) & 3 of Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?

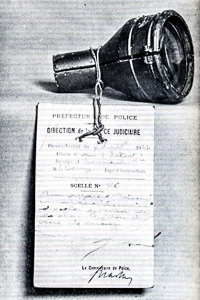

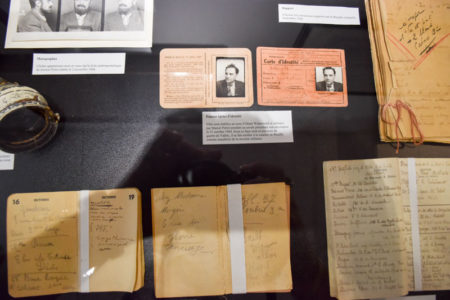

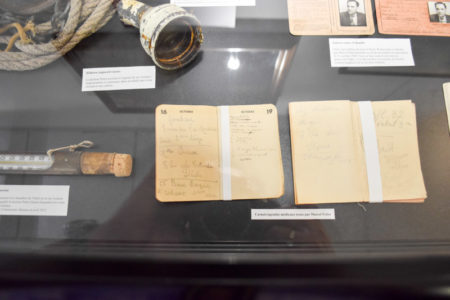

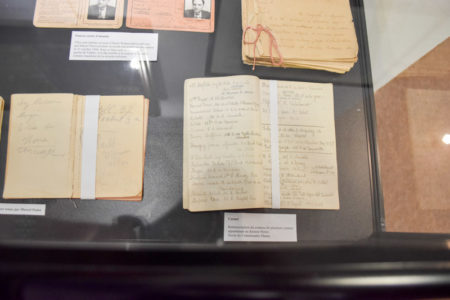

Some of the artifacts discussed in this blog found their way to the Paris Police Museum (click here to visit the museum web-site). Along with our friend and the best Paris guide, Raphaëlle Crevet (raphaellecrevet@yahoo.fr), we toured the museum during our last visit to Paris and spent several hours examining its exhibits dedicated to the history and forensics of the Paris police department. The majority of exhibits dealt with actual criminal cases of murderers, serial killers (including today’s subject), assassins, thieves, and other unsavory individuals. The museum covers the period beginning in the 17th-century through the present. An original guillotine blade is on exhibit. Located in the 5e, the museum is on an upper floor of a working police station so reservations are a must. Our visit to the police museum with Raphaëlle was so much better than our visit to the Paris Sewer Museum.

MEDIEVAL PARIS – Volume One & Volume Two

Let us take you on a visit to the Paris of the Middle Ages. Come walk in the footsteps of the men, women, and children who lived, worked, and played in medieval Paris. Stop and see the only three residences still existing from medieval Paris. Learn about the scandalous Nesle Affair. Many of the stops are sites that most tourists don’t know even exist.

Did You Know?

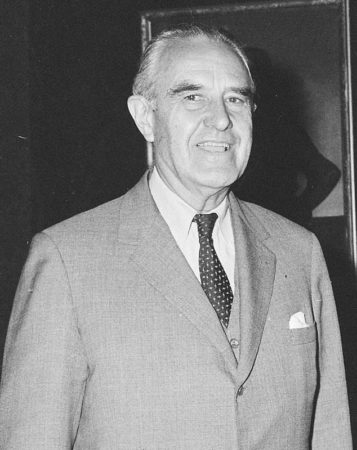

Did you know that one of Southern California’s largest car dealers was Cal Worthington and his dog Spot? Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Cal ran iconic television and radio ads featuring himself and Spot. Now Spot wasn’t a dog. Cal used a tiger, gorilla, birds, and elephants, all on a leash to fill in as Spot. It was a parody on a competitor who used pound puppies in his commercials. We always enjoyed watching Cal’s commercials for no other reason than to see what animal would show up as Spot. Cal formed his own advertising agency called “Spot” and it had only one client: Cal Worthington and his dog Spot. But this isn’t really why I’m featuring Cal today.

Calvin “Cal” Coolidge Worthington (1920−2013) served in the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) during World War II as a pilot of a B-17. He flew twenty-nine missions between 11 December 1943 and a Berlin bombing run on 29 April 1944. He was assigned to the 390th Bomb Group and 568th Bomb Squadron. Awarded the Air Medal five times, Cal was presented the Distinguished Flying Cross by Gen. Jimmy Doolittle.

As a co-pilot and pilot, Cal flew in twelve different B-17s (F & G) and not one was named “Spot.” He was promoted to captain in April 1944 and commanded bombing missions over Germany in the “Paper Doll” before rotating out and training other pilots including some of our first astronauts. Cal was one of the lucky aviators who made it home.

Thanks to Greg Smith (click here to read the blog, Rendezvous with the Gestapo) for alerting us to Cal’s wartime service and providing Sandy and I with a forty-year-old nostalgia trip.

Let’s Meet the “Good” (but Crazy) Doctor

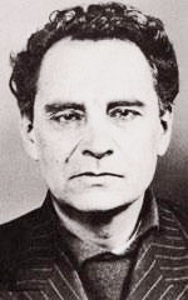

Marcel André Henri Félix Petiot (1897−1946) was born in Auxerre, France. During his childhood, Petiot committed many criminal acts including discharging a gun in school, robbery, and destruction of public property. It was also documented that he tortured small animals and enjoyed setting fires — all classic signs of a serial killer. Petiot was diagnosed as mentally ill and finished his basic education at a “special” school in Paris.

He served on the front during World War I where he was wounded and gassed. Sent to various rest homes, Petiot was arrested for multiple thefts. Thrown into prison, Petiot was again diagnosed with mental illness. So, what did the French officials do? They sent Petiot back to the front where he attempted to blow off one of his feet with a grenade. This exploit managed to get him honorably discharged. (Corporal Klinger from M*A*S*H certainly would have been proud.)

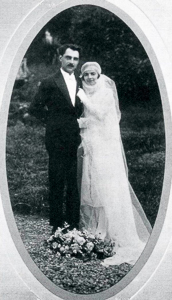

Petiot earned his medical degree in 1921 whereupon he set up practice in Villeneuve-sur-Yonne. He soon earned a nefarious reputation as a drug supplier, abortionist, and thief. He also likely claimed his first victim in 1926 ⏤ his girlfriend. That same year, Petiot won the mayoral election which gave him the opportunity to embezzle the city’s funds. One year later, Petiot married Georgette and within a year, a son was born. By 1932, the citizens had figured him out and he moved his family to Paris.

The Smoke and Smell

On the evening of 11 March 1944, five months before the liberation of Paris, Monsieur Marçais, resident of 22, rue le Sueur (16e), called the police over his concern for the immense amount of black smoke billowing from the chimney across the street at number 21. He was worried about a potential chimney fire in the unoccupied house. The neighbors later noted that the smoke had been heavy for the prior five days and the stench was nauseating.

Two policemen arrived on their bicycles and attempted to gain entry but were not successful. A neighbor who knew the owner telephoned him. Dr. Marcel Petiot lived at 66, rue Caumartin (9e), approximately fifteen minutes away by bike. He told the police to wait, as he would be right over with the keys.

After one half hour and no Dr. Petiot, the policemen were so worried about a fire that they called the fire department from which a truck and crew were sent immediately (the fire station still exists at 8, rue Mesnil). After smashing a window, several of the men were able to get inside the dark house. They followed the smell down to the basement where the most hideous scene unfolded.

The Basement

Two coal furnaces were blazing away with the dismembered remains of several humans inside. As the men looked around (lit by a flashlight), they saw skulls, arms, legs, and other human parts surrounding them. The odor and stench of decomposing bodies (or what was left of them) were too much. The police and firemen exited the basement and building.

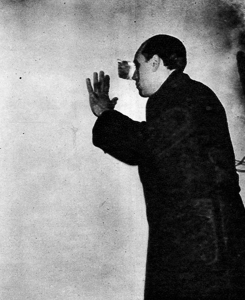

It didn’t take long for a large crowd to congregate outside the building. One of the onlookers approached a patrolman and identified himself as the brother of the building’s owner. He told the police that he knew about the bodies which he identified as Germans and French traitors. He managed to convince the policeman that he ran a large French resistance organization and then talked them into allowing him to take documents out of the building. Finally, the police allowed him to leave the scene on his bicycle after promising they would not inform their superiors about him. It was later that the patrolman saw a picture of the building’s owner and realized it had been Marcel Petiot who they let get away.

The Courtyard and the Pit

When the police Commissaire Georges-Victor Massu arrived, a tour of the basement (now fully lit up), courtyard, and adjacent small buildings revealed even more ghastly scenes. Carefully stacked piles of human remains were on the floor, a bag containing a human torso was discovered, and bloody tools were lying around. Leaving the basement, they entered the courtyard and went into a small building which contained a triangular room. There were no windows or furniture. The walls were very thick and imbedded in the walls were numerous iron hooks. A viewing lens had been constructed in the wall so that someone could stand in the adjacent room and view whatever was going on in the soundproof triangular chamber.

Moving on to the small carriage house, Massu and his team found a pit. A rope and pulley hovered above the pit. It was estimated that the depth of the pit was 12 feet. They quickly confirmed the pit was full of decomposing bodies layered with quicklime.

21, rue le Sueur

After moving to Paris, Dr. Marcel Petiot became a respected physician in the community. He bought the apartment on rue Caumartin where he lived with his family as well as maintaining his medical practice on the ground floor. He subsequently purchased the building at 21, rue le Sueur in 1941 and had extensive renovations done, especially in the basement and several other small outbuildings on the property. The surrounding wall was raised so that the neighbors could not see into the courtyard. A triangular room was built in the basement to exacting specifications, including only one entrance, thick walls, hooks embedded in the walls, and a peephole drilled into the wall to accommodate the viewing lens.

Petiot quickly built a reputation for smuggling people out of France and into South America. Unfortunately, the furthest his clients got was 21, rue le Sueur and the basement.

Occupation Activities

For years, Petiot passed himself off under various names, alias, and disguises. While practicing medicine, Petiot began an operation where he would promise to arrange safe passage out of occupied France to anyone who could pay his fee. Typically, these were Jews trying to escape deportation. However, there were many others, including gangsters, prostitutes, and even a 6-year old child, who sought out “Dr. Eugène” for travel assistance. He would always advise them to bring lots of cash and all of their jewelry. The first stop on their voyage was a visit to the basement of 21, rue le Sueur.

Discovery and Arrest

Shortly after the police discovered his basement in March 1944, Petiot went into hiding telling his protectors that the Gestapo was after him. He managed to elude capture until 31 October 1944 when he was taken into custody. Many rumors about Petiot circulated throughout the liberated city including murders he never committed, that he had been a Gestapo agent, and even that the story had been made up by the Germans for propaganda purposes. In fact, well before the city’s liberation, the Gestapo knew all about “Dr. Eugène” and gave the French authorities orders to arrest him.

Trial, Sentence, and Punishment

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3x4i48_H_To

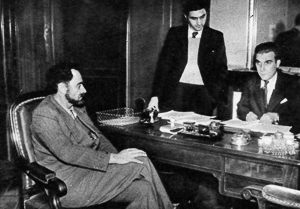

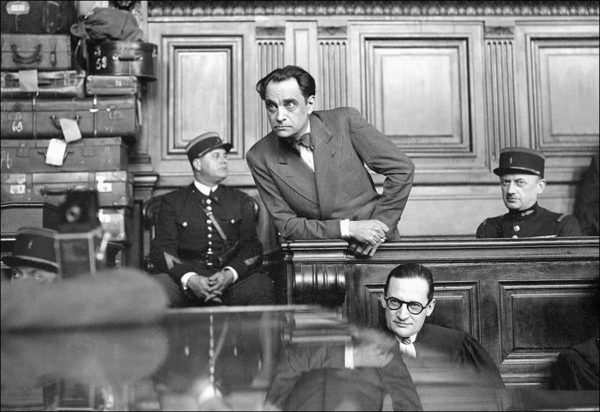

During his trial in March 1946, Petiot acknowledged and took responsibility for the murders. His defense was that he ran a resistance organization, and the victims were all German sympathizers or members of the German military. No one in any of the resistance networks could identify him nor could the authorities prove that any of the resistance groups he claimed to have belonged to actually existed. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GTAsOJwDbus

In the end, it was clear that Dr. Petiot was a serial killer (again and in hindsight, with all the modern day identifiable traits of a serial killer). Petiot was convicted of twenty-six murders, but it is estimated that his victims totaled more than two hundred. Two months later on 25 May 1946, Petiot was beheaded in the courtyard of the Prison de la Santé. Walking to the guillotine, he advised his attorney and others to turn away as it “wasn’t going to be very pretty.”

Click here to watch the video Outside French Court 1946.

Click here to watch the video Final Proceedings at the Petiot Trial.

Demolition

The authorities found hundreds of empty suitcases in the attic of Petiot’s rue Caumartin residence. The apartment furnishings could be described as upper middle-class, and Georgette wore expensive jewelry which she explained away as gifts from her husband. Although suspected of being an accomplice, Georgette was never charged and, in the end, professed an ignorance of her husband’s activities. No one has ever figured out where Petiot had stashed all the cash, jewelry, and other valuables he stole from his victims. Georgette and her son disappeared and were never heard from again.

The original building at 21, rue le Sueur was carefully demolished — brick by brick — in 1952. The person who bought the building was very deliberate in taking it apart. The buildings on either side are original from that time. You’ll notice the architectural style of the building sandwiched in between is quite different than the contiguous buildings.

Oh, by the way, the original basement remains intact.

Next Blog: “The Grey Ghost”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Kershaw, Alistair. Murder in France. London: Constable and Company, 1955.

King, David. Death in the City of Light: The Serial Killer of Nazi-Occupied Paris. New York: Broadway Paperbooks, 2011.*

Maeder, Thomas. The Unspeakable Crimes of Dr. Petiot. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1981.

Tomlins, Marilyn Z. Die in Paris. London: Raven Crest Books, 2013.

*Mr. King’s book was instrumental in developing the content for this blog. I highly recommend you read his book if you are interested in expanding the story of Dr. Petiot.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

We hope you enjoy this reprint of one of our more popular blog topics. If you’re in Paris and don’t have anything “new” to do, we suggest you visit the Paris Police Museum. As you read this, Sandy and I are in Tokyo and touring the city with a private guide. Hopefully, we’ll get our fill of sushi while here.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank our good friend from Scotland, Roland K. for commenting on our usage of the term “England” and clarifying for me the proper usage of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. Clearly, I was sleeping in class when the teacher covered this.

Blandine E. contacted us in March after having read our 2020 blog, Captain Jack (click here to read the blog). Blandine’s grandfather, Henri Cerisier, was a French policeman and résistant during the occupation of Paris. He arrested Guy Glébe d’Eu, count of Marcheret (a.k.a. Captain Jack) who was in collaboration with the Gestapo and directly responsible for the deaths of hundreds of resistance fighters. The count was also responsible for turning over downed Allied airmen to the Germans. M. Cerisier “hosted” American soldiers and one of them, Sgt. Arthur Pelletier, became a victim of Marcheret’s treachery. Sgt. Pelletier was arrested and sent to KZ Buchenwald as one of the 168 men targeted for execution (click here to read the blog, The Last Train Out of Paris). Fortunately, Blandine’s grandfather was not able to make the meeting of young French résistants in August 1944 to pick up guns and ammunition. Otherwise, he would have been massacred by the Germans along with the others. Thank you Blandine for sharing this information with us. I’m looking forward to our future discussions.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2024 Stew Ross